June 1, 2021

A Stroll through the Zoo of the Future

now welcome to the zoo of the future

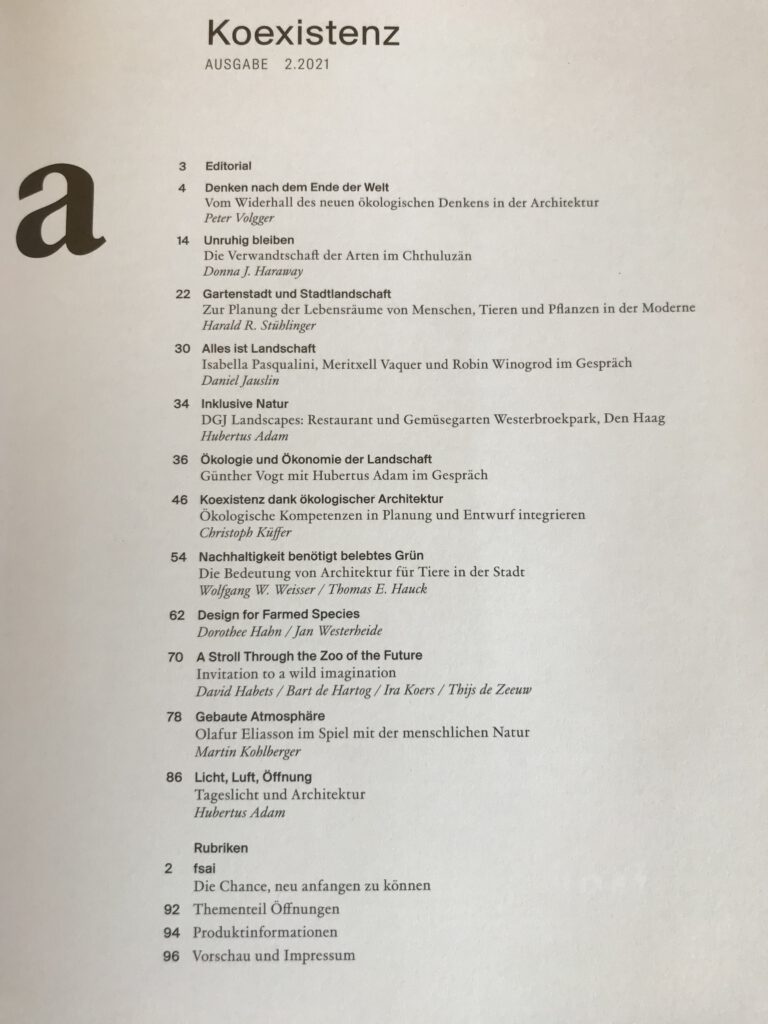

WELCOME TO THE ZOO OF THE FUTURE stands written in bright and shiny letters, on the arch under which we enter. The zoo for us, to use the words of Donna Haraway, is ‘an implausible but real now’ (Haraway 2016). A place where historic, contemporary and speculative human-nature relations can co-exist. Let us take you on a walk through these spaces that connect contradicting takes on our relationship with nature in past, present and future. We see the zoo as a living paradox. A vital one. We want to ask you, reader, where can we still meet animals in our cities? On our walk we want to leave behind zoos, as we have known them, and stroll into a space, not of captivation but of real encounter, whether it be friendship, conflict or mere toleration. A paradoxical place where wild urban animals and exotic species meet. To reach this space, we need to imagine new implausible -but real- nows, and visit ones from the past to find the courage to believe in a conjoint fabulous future.

2013 – 2017 urban elephants of Natura Artis Magistra

Our story starts at Natura Artis Magistra in Amsterdam. Strolling through the park, the director asked us to design a new exhibit for their Asian elephants. We wondered, how can we even know their needs? How do we make sure their lives are meaningful and worthwhile? How do elephants want to live in Amsterdam?

Over time Elephas maximus has adapted to its zoo life, slowly becoming Elephas maximus urbanus. The population is genetically carefully managed by the EAZA (European Association of Zoos and Aquariums), sending the bulls all across Europe. The endangered species breeding coordinator for Asian Elephants had summoned ARTIS to either enlarge its facilities or give away its female herd.

Considering their precarious cultural position, we decided to treat these elephants as citizens. The enclosure is not a representation of their natural habitat but an environment appropriate for a new urban future. The landscape that evolved (de Zeeuw 2017) therefore does not resemble any other elephant enclosure, but affords the habits of these enormous mammals. The enclosure develops their citizenship, provides food, offers numerous options for scratching their skin, challenges their spatial memory through complexity in form, colour and microclimates. Giving shelter in any wind direction, these anthropocene rocks created an urban elephant landscape that is both local and footloose, eclectic and instigates new ecologies.

2017 an ape theater

From here on we leave behind the zoo, as we know her. Between former dry docks, rusty cranes and flourishing ‘weeds, by lack of maintenance’ (Clement 2004) we walk towards a far more speculative space. On an old shack, a sign blinks in bold, colorful letters, ‘SEXYLAND’. Inside we find a temporary ape enclosure, designed as a place to think about the zoo of the future. Mindful of John Berger’s account of the ape theater at the Basel zoo (Berger 2009), the architecture of the gaze is reversed. Enriched with feeders with shot nuts, old car tires to bounce on, full of climbing affordances, for sitting and social grooming. An abstract jungle. An ape architecture.

That day in SEXYLAND we talked about the zoo of the future. Stories of (wo)men and animals were shared through poetry, science, film and virtual reality by artists, an archaeologist, a linguist, designers, researchers, a rewilder, a chef, philosophers, a futurologist and a herbalist who eventually ceremonially concluded the day through a both spiritual and bodily experience of the kava kava ritual. In our ape theatre we conceived four new directions, four paths to explore leading into future zoos. In the text, we will follow these four thematic paths: wilding the zoo, unearth zoo, a giraffe garden and the city as zoo (ZOOOF #1 2018). Together they form future speculations on the meaning of the zoo in the 21st century. They intersect each other in thought and cross one another paradoxically. This new zoo is far from complete, as we can imagine many more paths to take. We kindly ask you to read these futures as an invitation to contradict us, to debate, to design anew and most importantly to let your imagination run wild.

future now Wilding the zoo

Out of the darkness of the ape theater the landscape widens, loosely sprinkled, with various faux-roches standing tall in the post pastoral landscape. Ever since Hagenbecks’ panorama (Hagenbeck 1914), the rock has been the zoo’s expression of the pristine; emphasizing the wildness of the enclosed animals, creating a new architectural typology. But the rocks that we encounter now are not mere decors for animals to be presented in. Today they serve as a space for real, risky encounters, facilitating shared habits of both humans and other animals. Like eating, dying and sleeping together. In this ‘future now’ that we are entering, the zoo has become a place to ritualise our naturalness together with other animals.

future now Picnic rocks

We mount one of the more gentle outcrops, resembling the Rat Rock in Central Park. Like an enormous dining table it arises from the shrubberies in a seemingly forgotten wilderness. Staring at the skyline we feel comfortable and tense at the same time. Slowly becoming part of this long gone landscape, not knowing who else is roaming these hills, gives us a feeling of being both a hunter and prey (Kohn 2012). Adrenaline rushes through our veins, making us feel alive.

Back at the cave-like overhang where some remnants of a campfire are still smouldering in the ashes, we step out of the bright sunlight and hear a voice. “So Dinofelis must have specialized in hunting humans, but fortunately we humans have no predators left these days”. We stroll on and feel a confusing disappointment for its final disappearance. Did this enormous sabre-toothed cat help us understand our role in the ecosystem? Might there be fulfilment in being eaten? Did we maybe lose our connection with nature when we stopped being prey? (Plumwood 1995) And how come that it seems like the rock is asking us all those questions?

future now Vulture rocks

Lost in thoughts, after descending the outcrops of Dinofelis we move on. How can it be that the zoo traditionally showed so many forms of life but never depicted death? The absence of death illustrates our distance to nature as much as the fences that separate us from the others in the zoo. Without noticing we walk slowly up again. While overhead vultures circle on the urban thermal, it is hard to imagine that these enormous birds used to live in cages. Scattered over the hill, huge column-shaped rocks -like towers of silence- (Jivanji Jamshedji Modi, 1928) stand tall amongst wild grasslands. Here death and its rituals of grieve have become part of the zoo. In this sacrificial space, nature does not only concern what is around but as well the nature inside of us.

We witness a gathering of people. Some holding each other, some weeping while a body is hoisted up one of the columns. The past decades the zoo moved from an institution of captivity towards a place to become part of nature again. Here you can rewild your remains, vultures taking you on in the cycle of life, changing the zoo from a place of objectification into a sacrificial place of becoming earth again. On the distant sounds of singing people, the vultures come soaring in, landing on surrounding rocks. It is time for us to move on.

future now the oilfields of titan

From the beautiful brutality of the clean picked bones of the vulture rocks, we walk into a desolate space. With every step the natural seems to withdraw, until the colour of photosynthesis becomes totally absent. It is a space where desolation wraps around the self. Even the smallest sign of life stands out against the black tar lake that lies before us.

The route we have taken outward from our spaceship earth (Buckminster-Fuller 1978), we named unearth zoo. We walk into previously unrecognized natural spaces, from the oil lakes of Titan, towards underwater volcanoes, to the beginning of life in the shadows of passing meteors. Spaces which have been inanimate before, void of life, now spark with the dangers that life had to cope with at its beginning, in all its rudimentary forms. Travelling into this future is travelling into our past. As we walk on, we walk across giga-annums and into the devastations caused by our modern industries.

Can these tarblack fields show us love for the living, we wonder? As we step onto a simulated surface of Saturn’s moon Titan, this desolate place is reckoned to be one of the most likely places to find life beyond our earthly biosphere (Sagan 1979). Signs of life are found in rich lakes of carbohydrates that cover large parts of the moon Titan. These pools of oil on earth represent places of environmental devastation. A damaged image of nature, like oil spills caused by Shell in the Niger river delta, to name only one. It is a representation of neocolonial industrial strategies, an image that persists in the colonization of outer space. Life in outer space takes on an absurdly abstracted form. And yet, in the brutal sterality of outer space even the smallest signs of life spark our love for the living.

2010 the plants of Maxim Suraev

From these black lakes we enter a capsule, circling the earth every ninety-three minutes. In low-orbit, at four hundred kilometres distance from the earth’s surface, we lose our footing and float freely through space. The walls of the International Space Station are entirely covered with life preserving equipment, communication panels and laboratory set-ups (Scharmen 2019). An architecture entirely constructed out of ultra light metallics and man made synthetics. Except for a series of boxes floating weightless under bright lights, from which wheat and lettuce plants sprout. Their fading colours remind of a wintergarden and fill us with a love for life. As Edward O. Wilson described this particular love as biophilia (Wilson 1984), and it would be this love, which had to be revived in our society, that would protect us from devastating the planet we live on. Floating in this cold, disorienting space, we can only grab one of these boxes. Holding onto these plants, like cosmonaut Maxim Suraev cared and held his experiments (Johnson 2020). His arms wrapped around, with eyes full of love, reminding us of our love for life when we leave our earthly home.

1826 Zarafa and giraffe diplomacy

Back on earth, we land in the port of Marseille. It is 1826 when a ship with an oracular creature on board comes ashore. Is it a camel horse or dromedary? Zarafa came with her keeper Atir as a royal offer to prevent a territorial conflict. After overwintering in Marseille, where Atir bought her a two-piece yellow coat, they walked to Paris in forty-one days. The startling journey was amazed by spectators all over the country. It ended in the king’s menagerie at the Rotonde, a panoramic building with a 360 view on Zarafa’s living space. Although her arrival did not prevent war, she became an instant celebrity in Paris. Atir stayed with her till she died in 1845 in the Jardin des Plantes, where her remains are still on display in the lobby.

1871 Antelope house, walking through Systema Naturae

From Zarafas’ France we walk into the Prussian prince’s motley living collection of exotic plants and animals in Berlin. To display his gifts and trophies he contracted an engraver to literally translate Carolus Linnaeus’ system of classification of natural species, into a spatial diagram. Strolling through the Antelope house, its fairy-tale minarets stand tall amongst the surrounding trees. In the centre of the palace, twenty-one antelopes live together. From the surrounding corridor we see a zebra, an impala, a springbok, a wildebeest, a giraffe and other cloven-hoofed peers, housed in equally wedged rooms. We walk through this spatial narrative that traces out animals’ classes, orders, genders and species, characteristics and differences. A typology of defining ‘otherness’ that remains to be dominant in contemporary zoo’s.

Future now Giraffe Garden, how to monument

On the way we meet the keeper on his round. He explains how the theatrical environment of the palace deformed our encounters with others all those years. He tells us how humans obsess about giraffes that love doors because they are able to open them, but maybe giraffes just like open doors. He decided to give the entire palace to the giraffes, to open all the doors, to break open the ceiling to the skies and make a sandy floor. Light falls through the open arches of the buildings’ remains, as we carefully walk into giraffes’ living space. The antelope’s house has become a remnant against the backdrop of an urban savanna, a giraffe garden.

As we enter respectfully, giraffes gather around the entrance. Inside we witness a ceremony celebrating the interrelatedness of all species. The giraffe garden has become one of the hideouts in the city’s zoo reserve, filled with unknown hybrids of birds, animals and plants. It starts raining. The past months have been very dry and pools of water remain in the sunken antelope chambers. Giraffes join us in the ceremony, others bend over elegantly to drink. The cathedral-like space slowly has become a ruin, as time passes it will become a geological event, a layer of history like the bones of Dinofelis. In the future we will find these architectural bones and try to number and classify them. From its remains a new story will be constructed, telling how giraffes found common ground with humans in this garden of cohabitation.

future now The Way Out – the City as Zoo

Still glowing from the ceremony in the Antelope house we decide to leave zoo reserve. After passing under the arch with a shiny Z and three O’s, and an F, we walk back into the city (Greenaway 1985). To our surprise the road on which the animals once entered, chained and caged, is now an ecological highway leading out of the city. We walk onto a path where we experience the zoo as a city and the city as zoo. With the asphalt broken up, a porous network of soil has been uncovered in the cities’ streets, providing a home for all non-human animals. Hot summer evenings are cooler now with the water contained in the rich strip of vegetation evaporating. Even with torrential rains, the streets do not flood since the soil soaks up water. Where once cars, SUV’s and busses hummed over the asphalt, we now hear birds and beetles. An Insect highway, where butterflies are nipping on blossoming thistles, amphibians sunbathe on the edge of a muddy pool, while at the end of the street we see a wild boar run off with someone’s laptop. Here we are all free to go our own way. Whether this means staying in, or marching onwards to the ecological reserves outside the city.

1994 tinker nature in Erfurt

We walk uphill on the Northern outskirts of Erfurt, when something peculiar occurs. Looking down, enormous shadows are moving through the dense shrubberies. Sporadic creaking sounds of trees being uprooted, resonate in the background. Approaching the silhouettes, they appear to be a herd of African elephants skilfully stripping the south slope from its vegetation. By restoring the dry grasslands they protect native endangered species like red-backed shrikes, tiger beetles and numerous species of grasses. The elephants reside in the local Thuringer Zoopark and have become part of a Natura 2000 habitat, extricated from their African biotope they fight habitat loss in central Europe.

1933 The City as Üexkülls Oak

At the edge of the city we enter a forest, amidst we see a giant oak tree. Like a city, Jakob von Üexküll taught us an oak tree plays numerous roles in the life of different beings (von Üexküll 1934). If we look up to the oaks’ crown, we see where an owl made a nest. Below its roots, a fox dug its foxhole, to come home after roaming through the night. On the oaks bark, an ant is scanning its hunting grounds while under the bark a beetle is laying its eggs. The woodpecker splits the bark looking for the beetles’ larvae, where the ichneumon wasp lays its eggs, and so on. By seeing how one living thing can play seemingly endless roles in the lives of different beings, perceived by different bodies with different organs, we can begin to re-imagine our own environment to include more and more others.

If we try to leave our fixation on our visual surroundings and start perceiving our environment through vibrations, temperature, humidity, the types of light or the amount of butyric acid in the air, we might design differently. If we consider our kitchen the hunting grounds for fruit flies and birthplace of moulds, our buildings facades as porous shelters for birds and insects and our gardens the stopover grounds for monarch butterflies, we might be able to call ourselves a proper host of the big party we call life. We walk out into a city that resembles this oak tree, outward into many more implausible but real nows, lived together with all animals.

References:

Berger, John, 2009, Why look at Animals?, 1st ed., London: Penguin

Hagenbeck, Carl, 1914, Tierpark Stellingen, Hamburg

Habets, David, de Hartog, Bart, de Zeeuw, Thijs, 2018, ZOOOF #1 – The Zoo in the Anthropocene, Amsterdam, privately published

Clément, Gilles, 2004, Manifeste du Tiers Paysage, published in Sujet (2 juillet 2004)

Greenaway, Peter, 1985, A Zed and Two Noughts, London/Rotterdam, Artificial Eye

Fermor, Patrick Leigh, 1986, Between the Woods and Water, 1st ed., 166, London: John Murray

Fuller, R. Buckminster, 1969, Operating manual for spaceship earth, 1st ed., Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press

Haraway, Donna, 2016, Staying with the Trouble – Making Kin in the Chthulucene, 1st ed., Durham: Duke University Press

Jivanji Jamshedji Modi, B.A., 1928, The Funeral Ceremonies of the Parsees – Their origin and explanation, Fourth Edition, Bombay

Johnson, Michael, 2020 “Experiments with Higher Plants on the Russian Segment of the International Space Station”, NASA News release

Kohn, Eduardo, 2013, How Forest Think – toward an anthropology beyond the human, 1st ed., Berkeley: University of California Press

Plumwood, Val, 1995, Human vulnerability and the experience of being prey, pp. 29–34 Quadrant, 29(3)

Sagan, Carl, 1979, Broca’s Brain – the Romance of Science, London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Scharmen, Fred, 2019, Space Settlements, New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City

Uexküll Jakob von, 1934, A Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans, trans. Joseph D. O’Neil (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010). Original title: Streifzüge durch die Umwelten von Tieren und Menschen

Various authors, EAZA, Best Practice Guidelines for Elephants, 2020, Amsterdam

Wilson, Edward O, 1984, Biophilia, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.