February 13, 2018

In the early 1890s, Cecil Rhodes, the British imperialist and mining magnate, set in place plans for a zoo to be constructed on his estate on the slopes of Table Mountain in Cape Town, South Africa. Rhodes is remembered for his belief in the civilizing mission of British empire, and “the white man’s burden”. Recently he has been in the news via the events of #RhodesMustFall, a student-led social movement calling for the removal of a statue of Rhodes strategically sited at the pedestrian entrance to the University of Cape Town.

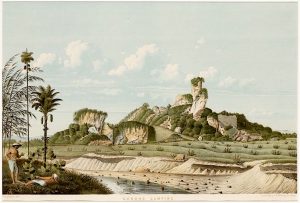

Like many zoos, the zoo that would come to be constructed on Rhodes’s estate was intended as a social and political statement. It collected animals from throughout the British empire, so that it constituted a mini-empire of animals. The spatial layout of the zoo followed a broadly metaphorical plan. At the bottom of the slope were ponds and cages containing the “lower” animals: crocodiles and wild fowl. At the top of the slope was the lion’s den, the king of beasts. Somewhere in the middle were the bigger mammals and the apes. In this way, the organization of the zoo was a bit like British empire itself, with its belief in the stages of civilization, and the division of humanity into lesser and more advanced races.

Rhodes identified personally with lions. He liked to be known as the “lion of Africa”. He had his architect, Herbert Baker, design an ambitious and impractical “lion house”, a collonaded structure meant to resemble a classical temple. Rhodes imagined wild African lions wondering free, set against the backdrop of this stirring architecture. The lion house was never constructed in this form, but as an idea it exists as a dense metaphor, that encapsulates several of Rhodes’s ideas. These had to do with the civilizing influence of the Western classical tradition, and the energy of wild African lions. The neo-classical architecture was meant to reference the Mediterranean worlds of ancient Greece and Rome. Rhodes dreamed that the Cape, with its Mediterranean climate, would become a white, Western civilization at the tip of Africa.

This project of projecting social and political ideas into natural worlds extended beyond the zoo, into the landscape of Rhodes’s estate. He imported 200 English songbirds to Cape Town in the belief that their birdsong would restore his health. He said: “It is my dream to fill my forests with the sounds of all the birds of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire… their song is nothing less than the song of civilization”. He also imported llamas, fallow deer, kangaroos and grey squirrels. The grey squirrels out-competed the local red squirrels, and have become a pest.

One of his most enduring legacies is a botanical legacy. Rhodes had three species of trees planted on his estate: English oak trees, a species of pine tree known “Stone Pines” or “Corsican Pines” which are native to the southern Mediterranean, and a local species of “silver tree”. Together they were meant to construct a hybrid landscape that – like the lion house – spoke to Rhodes’s dream.

Rhodes died in 1902, and in 1912 Rhodes Memorial was dedicated on the slopes of Table Mountain. Designed by Baker, it takes the form of a neo-classical temple. A double row of bronze lions flanks the steps of the temple, replacing the real lions that Rhodes had wanted for his lion house.

Rhodes Zoo, later known as Groote Schuur Zoo after the name of Rhodes’s estate, closed in the 1980s, and the lions were sold to a canned hunting operation in Namibia. For a while, the empty cages and enclosures of the zoo were inhabited by homeless people, until they were partially demolished by the Department of Public Works. Today Rhodes Zoo exists as a ruin. The largest surviving structure is the lion cage at the top of the slope. This continues to be inhabited by homeless people, and is visited by students from the nearby university to have sex and smoke weed.

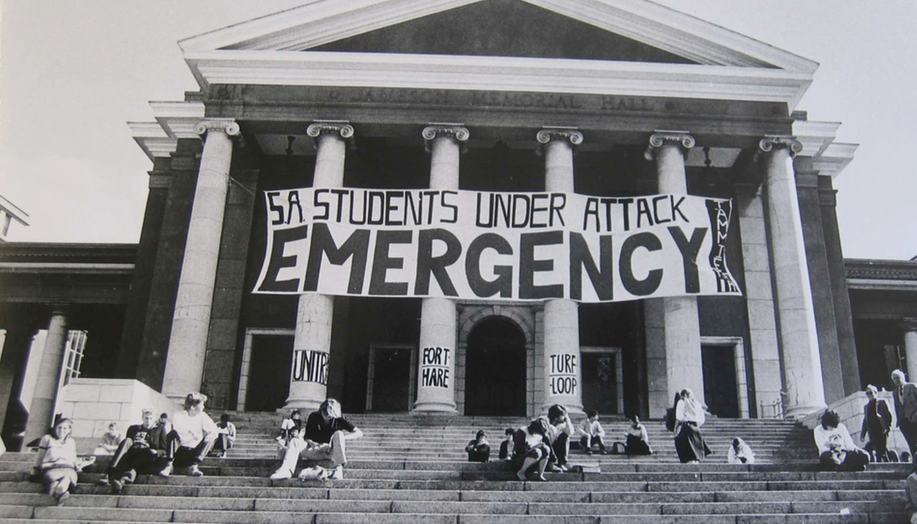

In the 1920s the University of Cape Town was constructed immediately adjacent to the zoo and Rhodes Memorial. It repeats the architectural trope of the temple-on-the-hill, with the university’s great hall – “Jamieson Hall” – taking the place of the temple or inner sanctum. Recently, the British publication the Daily Telegraph placed the University of Cape Town third in its list of the ten “most beautiful universities” of the world (Oxford was first and Harvard was second). In recent years, it has been the site of almost continuous student-led protests against the legacies of colonialism and apartheid.

My themes in this short account have been, first, the entanglement of natural, cultural and political worlds. Sites like zoos become powerful sites for the projection of social and political ideas. They become exemplary sites: living, material metaphors. They also become didactic sites, sites of instruction. Rhodes’s Zoo was meant to address, and to bring into being, a new South African public: white, English speaking, and filled with imperial zeal. In this way, it was as much an address to the future, as it was to the present.

A second theme is what I would call “the coloniality of nature”. This refers to the manner in which colonial and imperial projects extend into natural worlds, appropriating and transforming these worlds, and embedding themselves in plant and non-human animal species. Perhaps the ultimate form of imperialism is a kind of species imperialism, in which we bend non-human animals to human designs. Zoos like Rhodes’s Zoo present us with a powerful set of oppositions: wild versus free, safety versus danger, the everyday versus the exotic. They stage or enable or invite a potent set of affective encounters. The scripting of these encounters is often a kind of mastery. There is the being who looks, and there is the being who is looked at, who delivers up their private life for scrutiny.

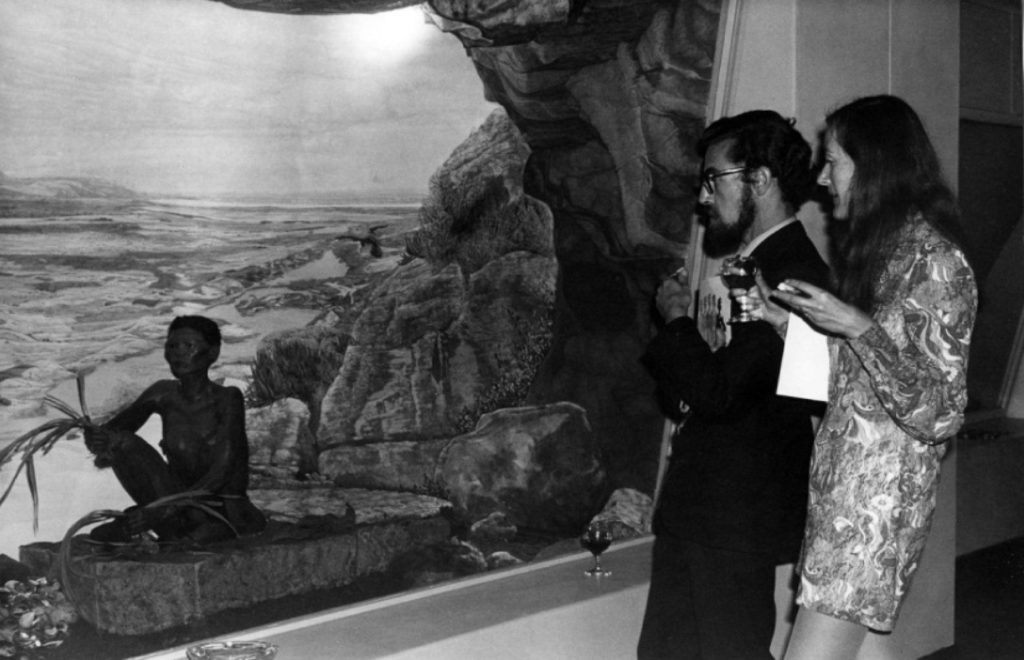

Historically, these ways of looking and forms of the gaze extended into human worlds, in the case of beings who were figured as not fully human. Human zoos and ethnographic displays, like the Ethnographic Hall of the South African Museum in Cape Town, became occasions on which white bodies gazed at black bodies delivered up for exhibition and scrutiny.

The idea of the Anthropocene is that this kind of mastery now extends on a planetary scale. Humans become agents in geological time and hold the fate of natural systems in their hands. The irony of the Anthropocene is that the moment of our mastery over natural worlds is also the moment of their collapse. As a result, we now live in a permanent state of emergency. This suggests that zoos might gain a new kind of power and potency as sites of looking and sites of encounter. Perhaps, for us, these will be excruciating encounters, filled with guilt and accusation, as we exchange looks with our accusers, those whose worlds we have destroyed? Or perhaps we want to be kinder to ourselves, and to see zoos not as stages for historically overdetermined encounters, but as something else: as life-rafts, perhaps, where human and non-human animals greet one another as fellow survivors. Perhaps one idea of the Anthropocene is to abolish the idea of wild nature itself, so that all that counts is to survive, and the whole world becomes a kind of zoo.

I want to make a point about the embeddedness of the idea of the zoo in a certain kind of history.

I want to suggest that the idea of the zoo is also the product of a second, broad historical context: colonialism. Colonial worlds gave rise to kinds of encounters, forms of affect, and forms of the gaze, that constitute a deep, and often hidden, part of the inheritance of the relationship between human and non-human animals. It is this that I am calling the coloniality of nature.

These colonial settings were also contexts in which human and animal worlds interpenetrated, in which some humans were regarded as animals, and some animals – like lions – were regarded as kings and symbols of empire. So that when we ask the question: What is the future of the zoo in the Anthropocene? Another way to ask this question would be: How do we decolonize the zoo? Or even: How do we decolonize the relationship between humans and other animals?